An interesting opportunity (now that investment portfolios have recovered some…and investors might find tax credits attractive) from a colleague in Washington.

Author: rickpace1

Sometimes we can’t get out of our own way

Absolute idiocy

Health Department Raids Community Picnic and Destroys All Food with Bleach

Rural Farming Lessons from China

China’s industrial growth has challenged the economic might of the United States, but the country’s advances have not occurred evenly. They have come at the expense of rural development, particularly in regions characterized by unfavorable natural conditions and fragile ecosystems. Although China has attained a high degree of grain sufficiency (about 95 percent) and remains a net food exporter, there are signs of enduring serious problems. Poverty combined with food insecurity and malnutrition continues to affect around 150 million Chinese people, according to recent estimates based on the World Bank poverty line of U.S.$1.25. This has exacerbated the widening gap between the wealthy coastal areas, supported by industrial development, and the impoverished peasants of the northwest and southwest who rely on subsistence production. In addition, agricultural income is generally declining and represents a lower percentage of rural household income; many farmers are losing interest in farming, with women and older people becoming the main agricultural cultivators.

Participatory research conducted in southwest China has resulted in concrete strategies to deal with these challenges. Farmers, led by women, have organized effective local organizations for technology development, seed management, and market linkages, with innovative support from the staff of public research and extension agencies. Collaborative field experiments to improve crop varieties—an approach known as participatory plant breeding—local biodiversity fairs, organic farming practices, new market channels, and new forms of research and policy support are contributing to improved farmer livelihoods and to a more dynamic and equitable process of rural development. Modernizing rural development using traditional and local knowledge stands in stark contrast to the shift to industrialized agriculture in China’s coastal regions. Both approaches will be needed if China is to address the challenges of food security, well-being, sustainable natural resource management, and biodiversity conservation.

The Article

Weeds and Industrial Farming…Turning Point

I just returned from the national meeting for weed scientists. It was a great meeting with a lot of excellent presentations. While a major emphasis at the meeting was on herbicide-resistant weeds, I was disappointed by the lack of emphasis on proactive resistance management.

In fact, a prominent weed scientist, whom I have the utmost respect for, made the statement that it was too late for proactive resistance management — that the cows had already left the barn. If he is right, farmers had better be on the lookout for a new profession. We must be proactive… in every field beginning this year. We can attempt to salvage what we have and go forward with a different approach.

The Article

Open Source Ecology

Applying the open source software programming idea to machine making…and doing it on a farm.

The Book of Jobs

An interesting Vanity Fair article by economist Joseph Stiglitz.

I agree with much of his thought. However, there is a deeply profound question that he leaves unanswered. I think as an economist he does not address the implications of his article.

The question: What social ethic does the American society implement to transition to a new economy? In essence, Stiglitz, as an economist, examines the political economy. Our salvation, in my humble opinion, lies in developing a new economic ethic that integrates the human condition and the natural condition. Investments in environmental economics, preventative healthcare, agro-ecology, and information technology (‘meaningful’ social networks) will lead the way. We need a genome project of our social intellect.

Google and Privacy

If you use Google, and I know you do, you may have noticed a little banner popping up at the top of the page announcing: “We’re changing our privacy policy and terms.” It gives you the choice to “Learn More” or, another option, the one I’m betting most people followed, to “Dismiss.”

Who wants to read about what Google plans to do with all that information it has about us?

I, too, clicked “Dismiss.” That’s because the very idea of considering what Google knows about me can give me heartburn. And if that happens, I may want to Google “heartburn,” and then I’ll wonder if my insurance company will find out that I was searching “heartburn,” or, worse, that one day I will apply for a new insurance company and the side effects of having considered what Google knows will result in a denial of coverage. But I digress.

The Article

Grandfather Reinstedler

Farming with Nature

This is a wonderful article on farming with nature…

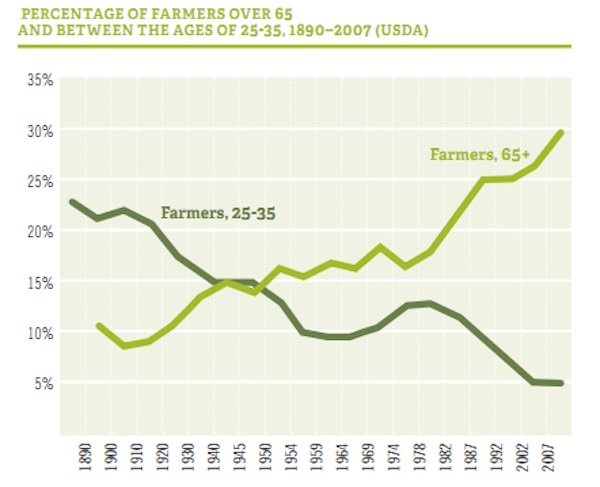

The Local Food Economy in 2 Charts

A very dramatic chart on the age demographics of farmers.

For both charts and this important Article